The acacia tree grows in the tropics and subtropics of five continents: North America, South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Long roots dig deep and hold the tree upright though erosion and the elements threaten to fell it. Sturdy branches stem from a strong central trunk, reach wide with all the leaves at the rounded top and earn it a nickname; the Umbrella Tree. Thick bark resists fire. In Africa, the acacia often stands alone, solid, spare, constant on the landscape. In Southeast Asia it grows in close crops, tightly knit together, in the jungle.

Part I

Deep Roots

East Africa, 2015

I met Sarah* at the at an international conference on collaborative solutions to global poverty in New York City. In a room filled with elite humanitarians, she is clearly youngest among them. Her black braids are pulled back to reveal a high brow, inquisitive eyes and a wide smile. The apricot blazer and periwinkle blouse she wears create a contrast to the standard New York business blues, grays and drabs of other conference attendees.

We are seated at a table with the Ethiopian Prime Minister’s son-in-law, a board member of the World Economic Forum from Paraguay, and two Nigerian philanthropists. After brief introductions, I engage Sarah, a law student from east Africa. “My organization produced a book featuring sustainable development work among families in your region. My favorite chapter is about a program created to reduce maternal deaths and the spread of HIV/AIDS.”

“I worked as a volunteer in a program like that,” she offers, eyes alight. “We gathered men from the villages to share the signs of maternal distress.”

Surprised at her response, I pull a copy of the book from my bag, open it to the chapter on maternal health, and place it between us on the table.

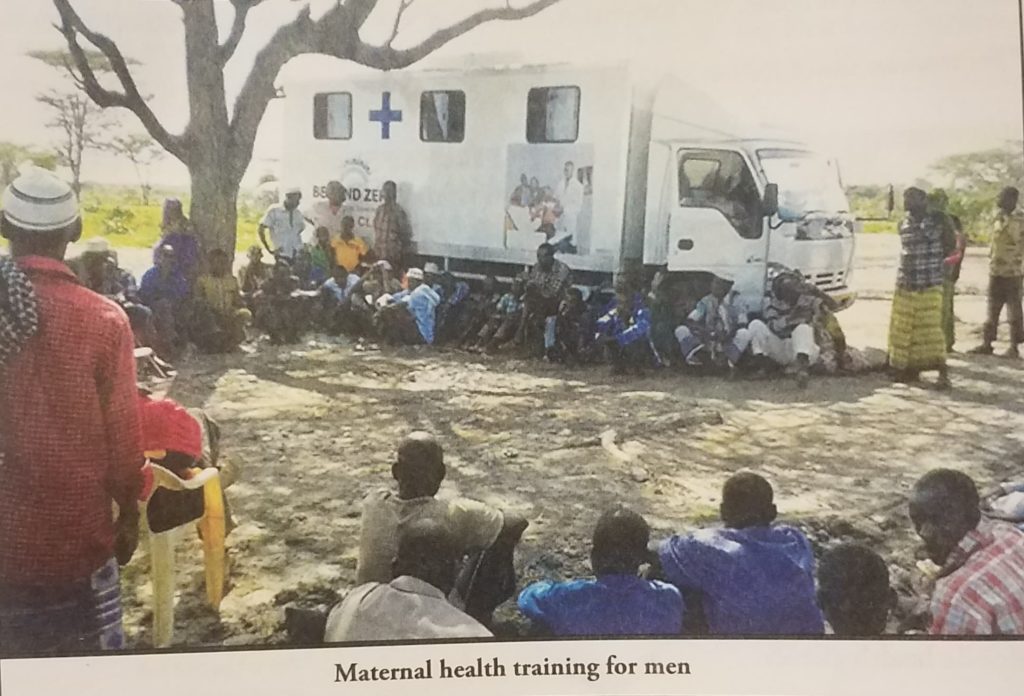

Below the heading “Best Practices – Full Participation and Involvement of Men,” is a short description of the program and its efforts to reduce the number of maternal deaths from childbirth. There is also a photograph. In the picture, more than 50 men sit at the roots of a wizened acacia tree; a medical-clinic-on-wheels is parked in the background. Sarah puts one hand on the page, scanning its contents, the other on her heart. “I helped in an effort like this.”

In February of 2015 Sarah and her team of volunteers enters a small village in east Africa. Their aim, the shelter of the village’s central acacia tree where most of the community’s action originates. At 19 years old her slight frame and childlike laugh make it easy to question how much she could know about the vital issues she came to discuss.

“I knew we needed to do something to get their attention.” In rural East Africa, men are not accustomed to taking lessons from school girls. She giggles as she recounts the story of how she grabbed the tether of a wandering cow and pulled it through the streets as she shouted, “Husbands and fathers! This is a matter of life and death. This cow needs your help. Please join us at the village center.”

Startled by the strangers, concerned with the shouted plea, and curious about the life and death prospects for the cow, a large group of men assembled under the sturdy limbs of the tree to hear what the visitors had to say.

One of the simplest solutions to the complex problem of maternal death involves helping the men in a woman’s life understand the signs of distress. When fathers and grandfathers put their understanding to practice, villages see reduced numbers of deaths and decreased rates of disease. In the shaded gathering, Sarah and the other volunteers shared the information they were trained to present.

“The cow was just an attention getter that day. And, it worked,” Sarah emphasizes as she closes the book and finishes the story. The men of the village followed her and the other young volunteers. They listened attentively. But more importantly, they actively contributed to the conversation. The surprise came when fathers and grandfathers added their multi-generational wisdom. At the roots of the Umbrella Tree they had more to say about indicators of maternal distress than the program facilitators had brought to share.

Maternal and infant deaths in this east african country have dropped dramatically since the program began. “All people need is time and a place to talk to each other. This program is successful because neighbors are willing to gather and tell their stories.”

*Due to the political nature of sarah’s work, her name, program, and precise geographic details have been changed to protect her anonymity.

……..

Part II

Sturdy Branches

Burma, 1986

Sein Nu tucked three of her children into bed at a neighbor’s home and crept into the dark of the Burmese jungle. It was June of 1986 and just hours before, local military officials questioned and beat her in an effort to locate her husband, a leader of the ethnic Karen resistance movement in Burma. Nearly due to deliver her fifth child, and with a three-year-old daughter in her arms, she silently made her way to the Thai border where she hoped to find safety.

Two of Sein Nu’s daughters, Kri Paw and Jenny Paw tell their family story. We sit on decorative straw mats in Kri Paw’s living room, eating cookies and drinking orange juice. Kri Paw remembers, “One of the men in the village was able to find my father and warn him that my mother was arrested.” She explains that her father came down from the mountains long enough to provide Sien Nu with the things she needed to get away. Although Kri Paw was only three years old at the time, she can never forget the shelter of the acacia branches in the dark of night, and their protective canopy in the day.

According to the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, the United Nations High Commission of Refugees (UNHCR) only refers about 1 percent of all refugees to other countries for resettlement. In 2016, Kri Paw and Jenny Paw, joined me at the U. N. Commission on the Status of Women to share their story and discuss ideas of fostering resilience in refugee families. Though their resettlement story is rare, their plight as refugees resonates with families in vulnerable situations everywhere.

Jenny Paw was born in the first camp her family settled in. She weeps at the retelling of her mother’s arrest and interrogation. Then, reports the struggle for security her family endured over a decade of moving from camp to camp. “Even when we left our home the army followed us. Our father stayed behind to protect our people. We only saw him once a year. We had to escape from two more camps because they were bombed and burned.” She can still smell the smoke from the fires set to drive them from safety.

It was not all trauma. Jenny Paw describes herself at seven, a basket strap pulled across her forehead, the basket full of household items on her back. One day in the jungle she wandered several yards in front of the group and encountered an enormous elephant. Running and screaming, her entire family, and others who were with them, followed her into the river. When they discovered it was an elephant and not an army they had just run from, a great laugh filled the space between them.

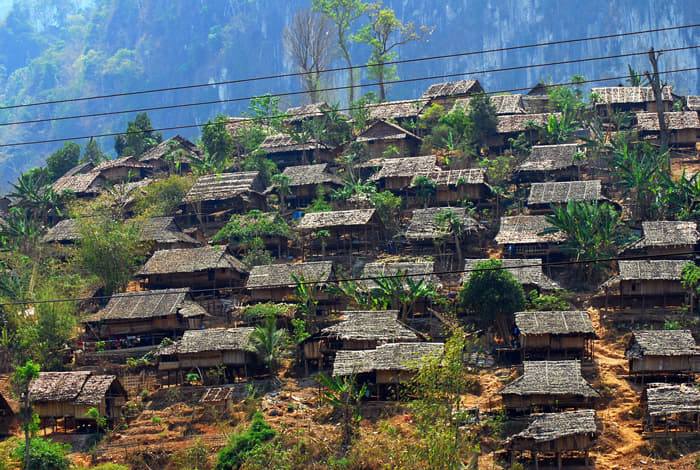

In 1995, the family arrived Mae La Camp, a sprawling settlement that is home to 50,000 refugees. With their father’s help they built their house of bamboo. Once the house was finished, he returned to his post in Burma.

Part of a refugee family’s success stems from their ability to work hard and problem solve. Sein Nu would rise before dawn to prepare a meal for her children. When they woke they went to the market in town and bought big baskets of fruits and vegetables that Sein Nu sold in the camp. “We gathered food scraps from our neighbors and fed them to our chickens and pigs. Then, we sold the eggs and meat.” When the family saved enough money, Sein Nu purchased a sewing machine and began a small tailoring business. Funds and fabric from that enterprise allowed her to keep her children outfitted in school uniforms and to send her daughters for further vocational training.

When Kri Paw was 15, she remembers begging her mother to allow her to go to Bangkok to follow her friends in domestic service. “She wouldn’t let me go.” Kri Paw says. “She said I had to finish school. I was so sad because all of my friends would come back from the city with pretty clothes and nice things.” With persistent encouragement from Sein Nu, Kri Paw became a teacher, Jenny Paw, a nurse’s assistant. Before coming the the United States, the sisters spent over 20 years in Thai refugee camps. Kri Paw met and married her husband. She bore two sons in Mae La Camp. In 2007, she was the first in her family to be approached by the UNHCR with a resettlement opportunity in the United States.

Over the last ten years, Sein Nu’s 5 older children have resettled in the United States. Far from the tight-knit cloisters of acacia, a new community of young immigrants from Burma branches into Salt Lake City, Utah. They work in bakeries, clothing factories, and glass manufacturing plants. They raise children, struggle with integrating cultures, and grieve the loss of their homeland. Sein Nu’s youngest daughter, Ta Da Paw, born in another refugee camp, stayed behind in Thailand. Through their combined efforts, Kri Paw, Jenny Paw, and their siblings raised funds to help their sister attain her Thai citizenship. Ta Da Paw received scholarships to attend Bangkok University and in March of 2017 she became the first college graduate in their family. 31 years since she took shelter in a jungle of acacia, Sein Nu still lives in Mae La Camp with her husband.

——-

Part III

Fireproof

Kenya, 2011

A Kenyan proverb cautions, “He who stands in the sun is a fool.” Jeff Power of Denver, Colorado sits with his back against the solid trunk of the village’s central acacia tree as temperatures rise. It’s 2011 and his organization has worked with the people of Gambella, Kenya for three years. His role is Director of Partner Development for Global Hope Network International. Jeff is tall and fair haired, with a light complexion. He wears glasses that can’t hide the laugh lines he has nurtured for years around his eyes. But, for now, laughter seems far away as he listens. He listens to voices arguing, to angry accusations, to the sound of his own heartbeat. As tempers flare his awareness heightens and he considers the machete each man keeps close at hand.

Under the tree, the flame of distrust is fueled by dead goats and desperation. It’s Jeff’s job to cool the situation. In an interview later, he tells me, “The villagers accused our Kenyan staff of pocketing funds. Corruption is a pretty big concern in the area, and when lots of goats died because of drought, they wanted us to provide more.”

Leaning against the stalwart trunk, Jeff doesn’t begin with proofs of oversight and auditing. Or, with information about Charity Navigator, the largest independent evaluator of U.S. charities, which rates Global Hope at 100% for financial transparency. Instead, beneath the shielding cover of leaves, he reminds the people of Gambella about their investors; families like their own, who have a little extra to share, who care about them and want to invest in their success. He also invites them to look at the books.

Tension does not always run so hot under the tree. The idea of investment calls the villagers’ attention to the progress they’ve made since partnering with Global Hope in a unique model. The model is called Transformational Community Development (TCD) and focuses on villages across Africa, Asia and the Middle East. In the rural areas of these regions, average income is less than a dollar a day. People living in extreme poverty are vulnerable to slavery, radicalization, and other forms of exploitation.

Jeff tells me, “All we need are coaches on motorcycles and we can help change the face of poverty on the planet.” Three L’s dictate the coach’s approach; solutions must be Low-cost, Low-tech, and Locally Available. A coach, always a dependable native of the region,commits to a group of villages for five years, then assists each village with the formation of five development committees: Food, Water, Wellness, Education, and Income, all run by men, and women, from the village. The committees lead their village to transform themselves out of cyclical poverty. Jeff says, “Five years, and they graduate. We don’t do it for them. We invest, partner, and coach. Then, they do the work of transformation. There’s so much dignity in that. They own the change they make in their village.”

When an Education Committee was formed, they learned the steps to start a real school. In 2007, the acacia’s expansive branches provided a place for children to learn with a volunteer teacher. The coach told the committee, “The government will pay for a teacher. But, they don’t send teachers to trees.” A plan was made to build the first classroom in the village. With matching funds from Global Hope, construction was soon complete and a teacher was sent to the village. Jeff remembers building the school as a unifying community effort. “The young mothers hauled large stones for its foundation while carrying babies on their backs.” One classroom became several with the help of other education-focused organizations. Then, the Gambella School Administration Building was built and paid for by the Kenyan government after the village proved their own initiative.

Other committees performed their work of transformation. Under the tree, women on the Income Committee learned basic business skills from their coach. They turned the common camel watering hole into a bustling business site with a tea shop built from straw and mud. They purchased tea from the market, made traditional pancakes, and sold refreshment to the men tending the animals there. Incomes for the women grew from less than a dollar to over ten dollars a day. The Water Committee learned low-cost, low-tech methods to purify drinking water to World Health Organization standards. With this change the village went from suffering one or more infant deaths a month to less than one per year.

Adversity can provide as much opportunity for growth as abundance. Jeff describes a final tense moment under the acacia. One night, a neighboring village raided Gambella, killing several villagers and stealing thousands of animals. It was a pivotal point. After past raids villagers sought retribution. This time, they held a conference, considered all their hard work, and chose a different way forward. Forgiveness. Jeff concludes, “In the intervening time our staff and government involved elders in fruitful reconciliation meetings. The people broke the cycle of violence and poverty for their village. Now, everybody looks to that village and learns from that village. The tribes work together. Gambella village has become a shining example in that whole area.”

——–

With a village, as with an acacia tree, sometimes strength is found in standing alone, sometimes in being knit together. Reinforcement comes from the depths of its roots, the sturdiness of its branches, and from its ability to resist fire.

Written by: Mariah Fralick