Forget what you think you know of speech therapy. Today we introduce you to a woman who is training future generations of speech pathologists, with a unique focus. Dementia.

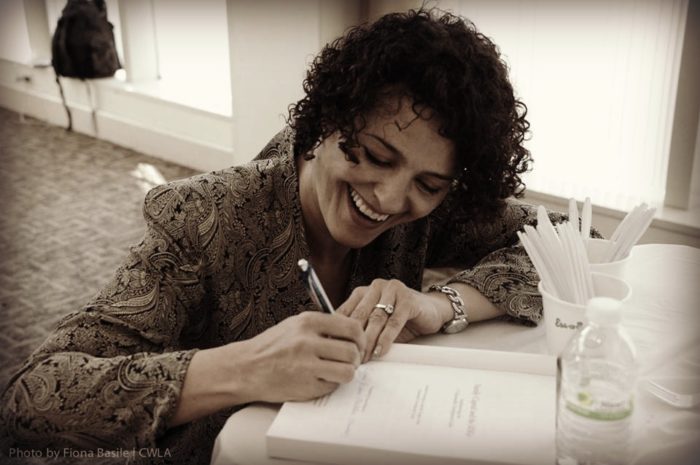

Some mornings, the coffee isn’t quite black enough for 34-year-old Amanda Stead. She readies herself, and together with her husband, rushes to get her children fed, dressed and off to school. “Don’t forget your lunch!” She hollers to her son as she takes a final sip on their way out. A ten-minute drive, two kisses, two hugs, and one “Have a great day!” later, she heads to her school, Pacific University. There, as Associate Professor, she guides this year’s students through the curriculum she helped create. Later in her day, she researches, attends meetings, and checks in with programs she piloted in various memory facilities.

Slumped in a chair, Joe gazes out the window of his room, the food on his tray disregarded again. Though the assisted living facility is as lovely as can be, and the helpful faces friendly, at eighty-years-old, this is not a place he knows to call home. Fear and anxiety brew in his stomach. Even swallowing is a chore, since the dementia swallowed him. Though far from being a child, he is not allowed to do much of anything for himself. With no memory of family or friends, his life revolves around the present moment, and in the brief glimpses of days gone by.

The nursing staff, friends and family, while kind and well-meaning, are stumped. They wish he would eat. They ask questions he can’t remember the answers to, and don’t realize that by doing everything for him, they unwittingly strip him of his joy. Enter Amanda’s team of graduate students.

“We’re really good about being fatalistic about a diagnosis of dementia.” Amanda says. “We’re so sad about it, that instead of doing the interventions, instead of creating an environment where people thrive, we just give up. We say, oh, this is terminal…even though that may take 8, 15, even 20 years—If the goal of all our lives is to live the best life, then why is it we give up on people after a diagnosis?”

Her team walks into the gentleman’s room, and place sandwich making materials on a table. They turn on some Frank Sinatra and crank it up. They smile, say hi, and get to work on those sandwiches. In no time at all, Joe is smiling, laughing, talking and dancing. He spreads peanut butter on one piece of bread, jelly on another. He slaps the two pieces together. He takes a bite, swallows. Life is good.

Amanda teaches speech-language pathology with a focus on the relationship between language and Alzheimer’s—a study which was inspired by her own grandmother’s passing from the disease, and from a question. “I wonder why speech pathologists are not serving this group of people?”

When people think of speech pathology, most think of little children with a stutter. They don’t imagine the elderly woman who cannot remember what she did before breakfast this morning, let alone last week.

“Speech pathology is basically anything that impacts the way you communicate with another person. That means the way that you communicate outwardly, and also the way you understand how people are communicating with you.”

From her research, Amanda has found that people can and should be independent for as long as possible after a diagnosis of dementia. People who are given nothing productive to do, do something unproductive, or get anxious and agitated. “The body has a need to work. There is a positive emotional benefit that comes when they complete a task.” She says.

Dementia is the fastest growing disease in the United States and is the sixth highest cause of death in Oregon and in the US. One out of every three of us will have a close family member with dementia. Which is why Amanda is “committed to training generations of speech pathologists who know how to do this good work. We have to do this work, because the population is coming, whether we do the work or not.”

In a world that wants to focus on a cure, it can be exhausting to convince people that the process of helping those who are living through it is just as important. But once caregivers see it, they believe it. Specifically, it is us as caregivers, family and friends who need to change the way we engage, to create positive interactions.

An older woman is given a load of laundry to fold. She picks up the towels and can’t quite fold them perfectly. But she is smiling, she is actively engaged in her environment. That is the goal; much as the old cliché, it’s not about the destination, but the journey. In this case, it’s not about the result, but about the process.

Even though there are road blocks, for Amanda, in her words, “It is the best work of my life.”

“What a gift…all regrets, all burdens, gone. The only thing that exists is a moment, a single moment, so if you can make that moment a good moment, you are living the good life.” This is what her work has taught her, and what she holds on to as she kisses her children goodnight.

Written by: Katie-Rose

When women get together in order to do good …our world will prosper and change! Keep on doing!